Photos by Saturn + Sun Collective.

This essay is a loose transcript from my gallery talk at Tennessee Tech’s Appalachian Center for Craft for the closing of my exhibition, Where The Line Falls Slack, on November 12, 2025.

(Welcome + thanks)

In my practice, I use traditional weaving patterns associated with the American South to talk about loss, class, and individualism. I grew up in Georgia and now live in western North Carolina. I got my BFA in Fibers from Savannah College of Art and Design, which was moderately craft-focused. There was focused attention given to traditional weaving practices and material interaction that laid the foundation for my aesthetic interests. I then went on to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to further my studies and begin researching what was driving my work, which was primarily focused on globalized labor and the contemporary garment industry. Since then, I have worked with found material as well as fabric I’ve woven on my loom.

In 2023, I had a major shift in my work, when my estranged father died suddenly. I had never thought to make work about the south or anything informed by my working class, conservative, evangelical upbringing until then. My brothers and I went to help my mom sift through my dad’s belongings, and I was confronted with an exaggeration between my memory of him and what he’d become. Through his books and collected objects, I was reminded of his being a product of his time and place - being born into the segregated south and attending Robert E. Lee high school (now Upson-Lee high school), and ultimately holding fast to a neo-confederate identity validated by the culture surrounding him. As a way to process my grief from his life and death, I started to make work about our relationship which utilized material I collected from his woodshop. This was the first time in my practice I attempted to tell a simultaneous personal and sociopolitical story that felt connected. This was, of course, in the middle of Trump’s resurgence.

This exhibition feels like a continuation of that work. I am still putting these narratives, both personal and historical, against the backdrop of the American South and southern Appalachia. I’m using the same processes: floor loom weaving and digital weaving. I’m also interested in the idea of fabric as inherently sculptural and confrontational in its form. What’s different, though, is that this newer work is more of a reflection of a collective grief than a distinctly personal one.

The title from this show, Where The Line Falls Slack, initially came from a formal interest. I think one of the primary things that interested me about fiber, over a decade ago now, is the way that the material behaves. How it responds to gravity, touch, exposure - as an individual unit (as in a thread) versus as a collective whole (as in cloth) - is pure poetry to me, and serves as a metaphor for our bodies and for the systems in which we live and fall susceptible to. I was thinking about the loom as a device that first and foremost holds tension. Anything we do on the loom can be done off the loom technically - it’s the slack that complicates things. A weaver needs tension in order to make sense of the warp and weft thread. I was thinking about this metaphor in relationship to American notions of individualism. Specifically, the idea of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps” comes to mind - a phrase popularized in 1834 which was immediately understood as hyperbolic, surreal, impossible. Yet today, it’s been co-opted by conservatives to will the working class to miraculously succeed against the odds fashioned agains them. Another consideration for this title comes from Glenn Adamson’s Soft Power Essay, in which he likens the draping thread of 1960’s fiber artists (like Jagoda Buic, Magdalena Abakanowicz, and Lenore Tawney) to the flaccid penis in ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman sculptures. He hilariously makes the case that “what goes down must come up” - this softness is understood inherently as a deficiency, or as point in a system in a relaxed state.

There is some theoretical groundwork for this title and this idea, but the theoretical became personal when Hurricane Helene struck Western North Carolina last fall and made these ideas a reality. In the aftermath of the storm, I witnessed in person and from afar (while teaching in Richmond) neighbors rallying to repair roads, deliver insulin, locate loved ones. I also saw businesses hoard and violently protect material goods. There was a spectrum of responses to the storm in WNC, this moment of mishap, or slack in the line, that affected all of us.

Come Hell or High Water

2025

Hand-woven cotton and linen, western North Carolina clay beads and dirt (made in collaboration with Melissa Weiss)

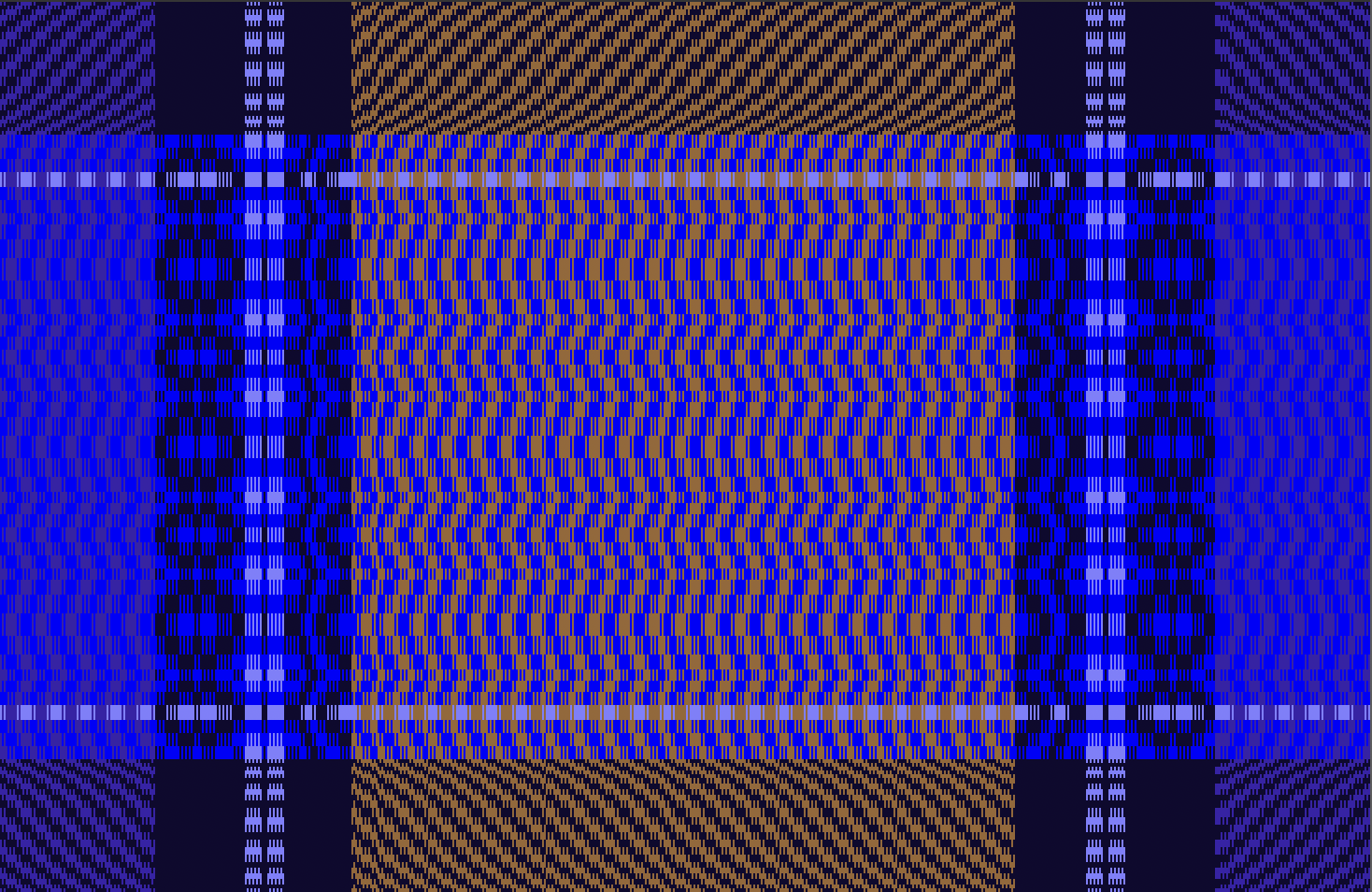

Digital weaving draft for Come Hell or High Water

I want to speak technically about the patterns and styles of weaving we’re seeing in the gallery, as most of you are weavers. My current work draws primarily from southern and southern Appalachian overshot weaving drafts that I’m mimicking, remixing, or antagonizing in some way.

There have been three primary handweaving revivals in the United States. The first was in the 1870s and was connected to a colonial revival more broadly. The second occurred in the 1920s and came from an interest in Appalachia, fostered by settlement schools in which Appalachian women sold blankets and coverlets to support themselves. There was another revival around 1976, The Bicentennial, which emphasized the Scandinavian tradition.

My research is focused on this one in the middle, primarily the work of Frances L. Goodrich, who came to western North Carolina from New York to help “civilize” the mountain women here. Famously, she collected patterns from the women of Brittain's Cove (in Weaverville) and compiled them into her “Brown Book”. Her efforts in western North Carolina became Allanstand Cottage Industries and provided a livelihood otherwise unimagined by these newly-empowered women. These patterns are synonymous with Appalachian craft history, but of course they were brought over by immigrants (mostly from Scotland, Germany, and England). Many of them were originally drafted anonymously and we know little about their origins or the weaver’s intentions for them.

Returning back to Hurricane Helene - several of the pieces in this show are a direct response to the storm. Come Hell or High Water was a collaboration with Melissa Weiss. After the storm, I felt an urge to write a weaving draft in the traditional style of southern Appalachian overshot weaving. The history of weaving in this region is marked by notions of heritage, nature, and political events. This felt like an event worth remembering. I knew that I wanted to have motifs in this pattern that referenced water, transformation, the red clay that permeated everything after the storm. I also knew that I wanted this to teeter on the ledge between traditional and contemporary. When I started weaving, I knew that I wanted to have two planes that were going to interact in space, but that’s all I knew. Working intuitively felt important for this piece for reasons I couldn’t name then, but now know that I had to figure out how to problem solve rather than plan my way through this metaphor for survival. After weaving, I worked with Melissa and her partner Elijah to dig wild clay from a flooded riverbank near their home in west Asheville. We made clay beads on their dining room table, and Melissa fired them. With the remaining clay, two sandbags were packed and sewn into the weaving. The sculpting of this piece was perhaps my favorite moment of this show coming to be - to me the final form references early warp weighted looms, a notion of protection, and planes of our past, present, and future in reflection of this biblical event.

On the anniversary of the flood, there were public grief events including one where folks gathered on a bridge and screamed at the French Broad. I get it. I really do. But my response was the antithesis of that rage. I felt a grief so big it felt like it swallowed me whole. This storm that climate scientists are crediting to human-caused climate change seems like there is a guilty party, and it certainly isn’t the river. I am thinking of this piece as an offering of pennance, as a shroud of mourning.

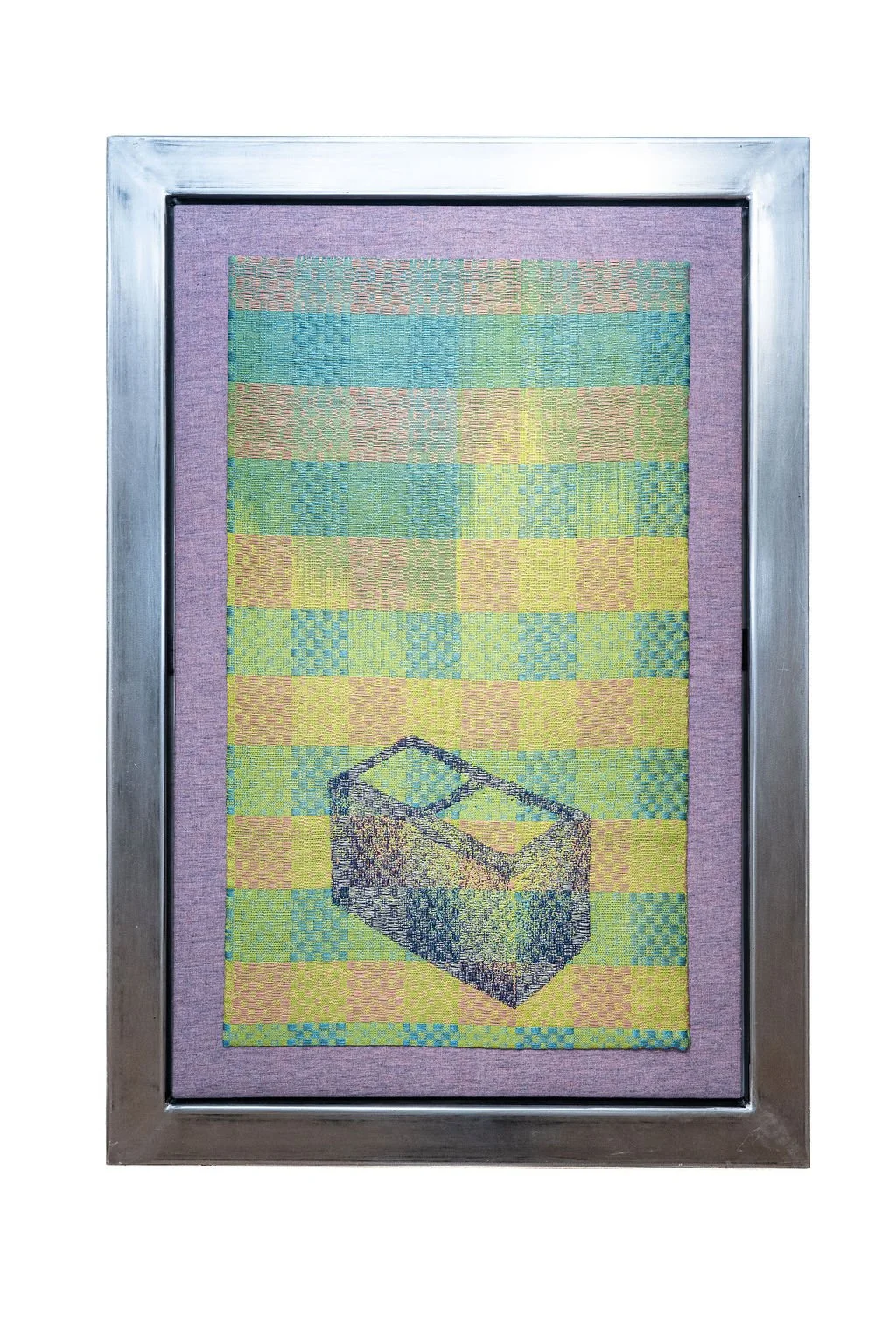

From Which To Build

2025

Hand-woven and hand-dyed cotton and linen, linen backing

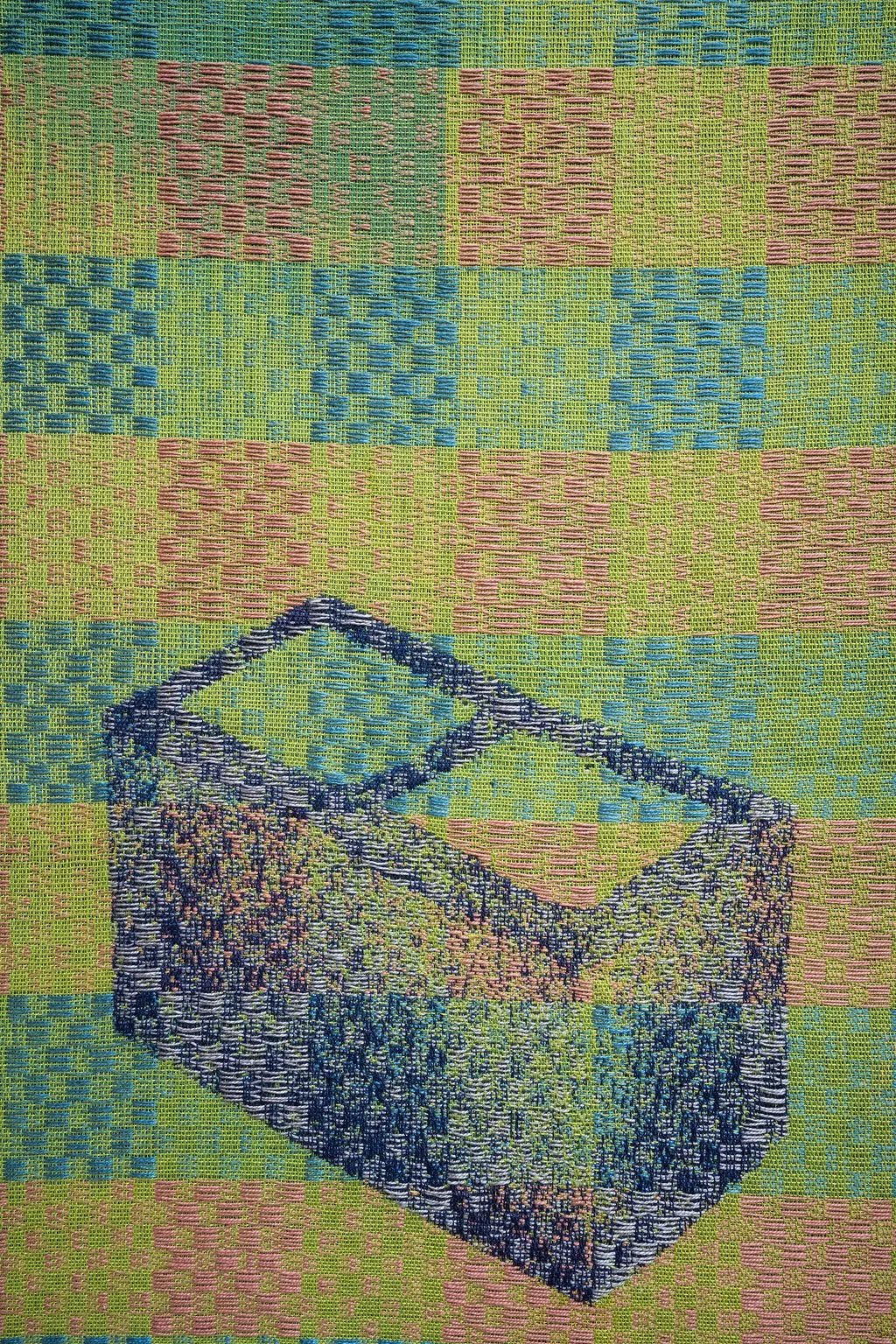

Detail

The second piece that I’d like to talk about in this exhibition is From Which To Build.

I want to speak about this work technically for a moment. As you can see, there is a clear representational subject matter of a cinder block in this weaving. Many of the pieces in this show are photographic in their subject matter, which for my work, is done on a TC2 loom using Jacquard technology. I’m going to be a little vulnerable in saying that I’m not quite sure what the future of my subject matter will look like, but it’s something I’m thinking a lot about. For this show specifically, I knew that using these found and altered images as subject matter felt right. I am interested in the way that the texture of the object or scene weaves in and out of the pattern, merging the planes of figure and ground.

After the storm during one of my first trips home, I went to the River Arts District in downtown Asheville. Although I don’t have a studio there, I felt a distinct pull to see the creative hub of the city that was one of the reasons I wanted to live in this region. There were many piles of cinder block and brick rubble - monuments to the storm and its power. It was hard to distinguish which piles were which buildings. It would’ve been impossible to know if not for the nearby empty lots.

I photographed these piles of rubble and tried to weave them several ways - they all came out wrong and felt inherently violent. There are so many people who have written on the ethics of showing trauma or its aftermath in artwork (Susan Sontag and Derek Jarman are two I look to), and I believe it was the violence of the scene that was coming through in the first iterations of this idea. Instead, I started working with the singular cinder block as subject matter. What is a block without other blocks? What are we, in times of catastrophe, without one another?

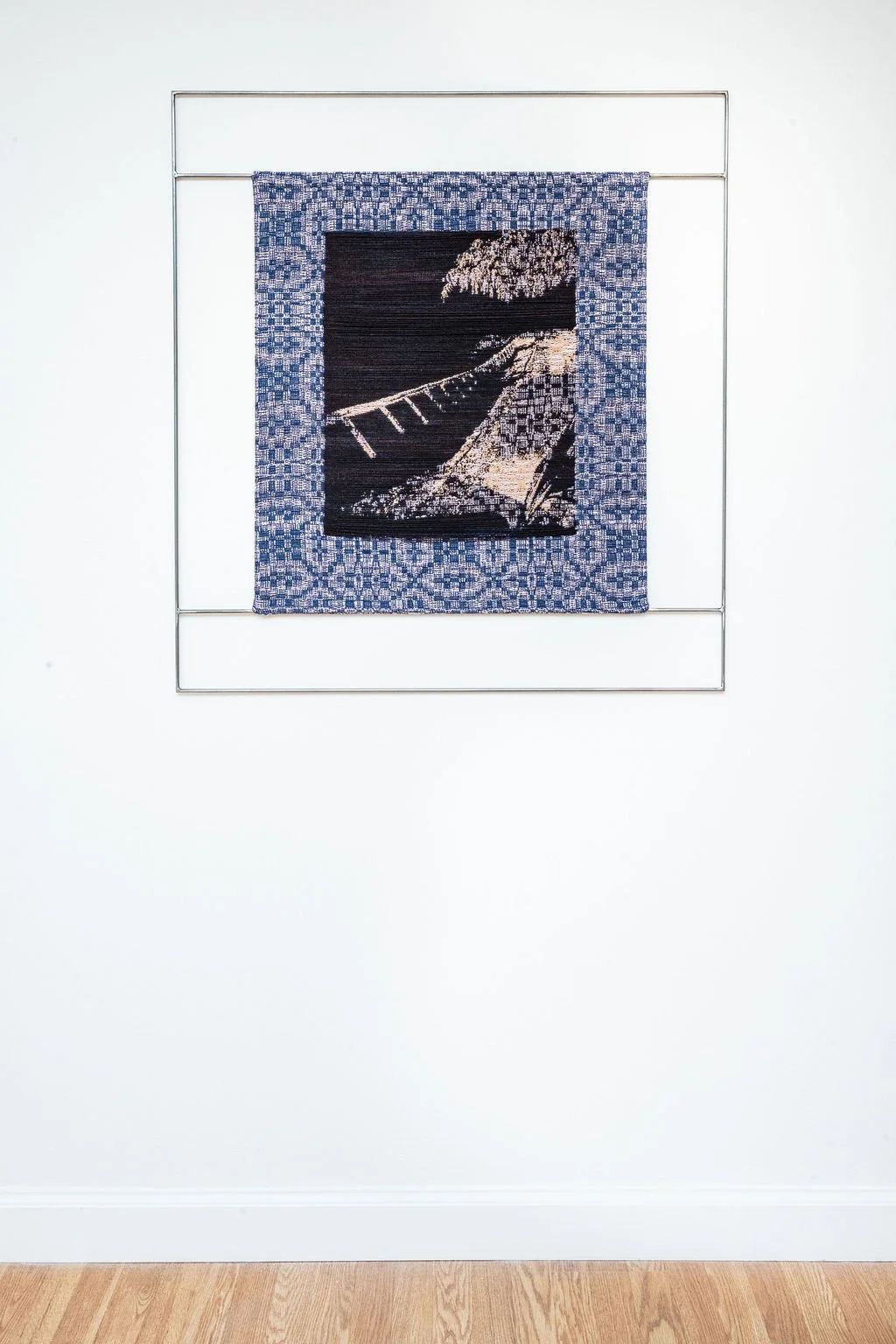

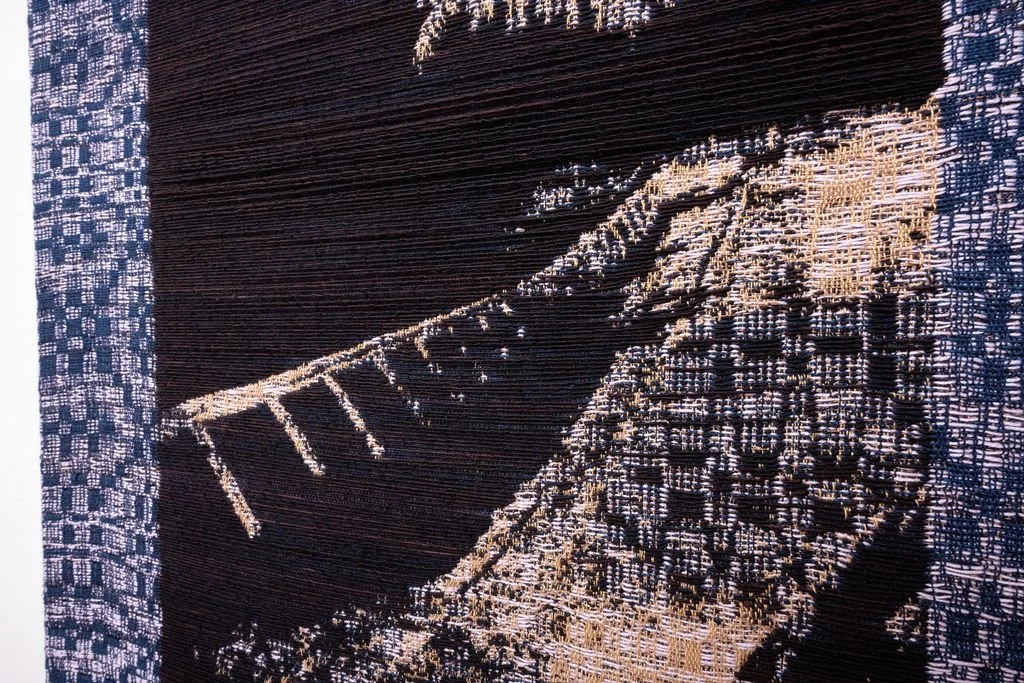

Offline

2025

Hand-woven and hand-dyed cotton and wool

Another piece in the show that responds to Helene is Offline. In the wake of the storm, especially when I couldn’t get in touch with my loved ones, I was scouring the internet for any inkling of what may be going on in the valley that I live in, or in Asheville where many of my friends were. This endless scrolling process was compulsive, but it also alluded to the internet of old. It felt, for a moment, like the pre-surveillance capitalist internet did, when people would spend hours responding to forums on mySpace or Reddit. When the internet didn’t have all the answers, but when actual people did. There was something poetic about that habitual mining of information after the storm. This image came from that - I pulled it directly from Reddit. It was captioned “This is why you shouldn’t be driving in NC right now”. The perspective is from the driver’s side of a car on the right side of the road, the left lane completely washed out and the guardrail barely hanging on in the void of night.

This overshot weaving pattern (the blue and lavender border that weaves in and out of the scene) is from Frances L. Goodrich, but is believed to have been drafted in Connecticut. It it called “Ferris” and is named after the woman who drafted it. She wrote and wove this pattern to make blankets to raise money so that she could hire some local men to blow out the side of a mountain that bordered her property. There was a river on the other side of the mountain, and she wanted fresh water for her cattle. It’s not clear if this was ever acted upon, but I love this anecdote and I think there’s a reason it survived and resonated with the women of Appalachia. Like I mentioned, there are very few historical tracings of these patterns, but several have anecdotes like this to accompany their documentation. I think this one, in particular, speaks to the ways in which we project ourselves onto the land. The contemporary image of the road after the storm is a reciprocal image - showing how the land projects itself onto us in turn.

Q+A

When do you decide on presentation? Do you know the work will be stretched versus sculptural when you’re working on it?

I rarely know matter-of-fact when I begin working on a piece what its final form will be, but I have noticed that if a piece feels like a drawing or an image, I tend to stretch it so not to complicate the subject matter. This is something I hope to challenge in upcoming bodies of work. Other times, I am working larger and it’s more about structure and material behavior, and I work more intuitively through these pieces. That process is scary, which is probably why I oscillate back and forth. Working on the large sculptural pieces are the most memorable pieces to work on, though - the flow state invited in by play and continuous problem-solving is hard, but the good hard. For example, in Come Hell or High Water, I was restricted by the width of the loom, and I knew that I wanted to have two “arms” produced by a slit-tapestry-like technique of discontinuous weft while weaving. I wanted this to feel like a fractured traditional weaving, and that I wanted to add another element of material specificity through wild clay. I made one decision at a time and would try out the possible solutions beforehand, photographing and drawing on the photos continuously until it felt right. I think this is one of my favorite pieces in the show because of my memory of making it. It was exhilerating.

How do you deal with people coming into your studio who may not have a respect for the south or craft and how do you respond to that?

This happens every now and then unfortunately. I was recently at a lecture about southern art and culture and learned that in 1949, a curator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote, “little of artistic merit was made south of Baltimore.” I think some people actually believe this today, and I think it stems from a classist mindset. If a curator is not willing to sit with the work and have some curiosity, then I probably don’t want to work with them. I will also say that curators and artists are symbiotic - if it’s clear that they have a hole in their understanding of visual culture, it’s our job to facilitate those conversations. Don’t be afraid to send a reading with a follow-up.

How do you approach color in your work?

I have been afraid of color for a long time. In the beginning of my training as an artist, I clung to high-contrast monochromatic color schemes. In graduate school, I felt intimidated by color and the notion that every choice had to be justified. I think the last few years have been me coming out of that spell. I really enjoy building color palettes now, and do think of a show holistically when considering how color choreographs you and your eye through the space. A few years ago I made a series of work in which I dyed and wove denim with experimental and exaggerated weave structures. That process connected me to the color blue, and I always felt like it was some sort of baptism of the material I was using. I don’t think I can ever stop using blue in my work. I like to use a spectrum as well - shades found in nature and shades that are disgustingly commercial. A color palette is a cultural marker - how do you represent the south in color? How do you represent loss? The land? Its myths?

What are you thinking in terms of sourcing?

For awhile, I was only using secondhand fabric and garments, but when I returned to the loom after grad school, I sought to buy as much secondhand and deadstock yarn as possible - mostly from Craigslist and Facebook - in order to attempt to not buy new shit to make new shit. My material sourcing is not perfect, and I still do have to supplement my material, especially when weaving on the TC2 loom as it requires so much consistent warp.

I taught at VCU last year, and there is something permeable about the Craft/Material Studies students’ thoughtful material sourcing and it really rubbed off on me. So much so that I actually started my own small flock of sheep this summer on my property. It will be a small amount, and will need to be dyed, but I am eager for adding something to my practice that will slow me down and connect me more with the place I’m making my work about.

You talked about your undergraduate experience being more craft-focused and your graduate experience being more contemporary; it seems like you’re combining those now in your practice. Can you speak to the way in which research and material tradition contribute to your contemporary practice?

I recently had a studio visit with a curator who told me that I “didn’t need the research” as I was explaining what my work is about and in conversation with. What I think they meant to say was, “You don’t have to use your research as a crutch”. I think the key, that I sometimes forget, is to be the connector - how does this research speak to larger themes in the work that are universal? The irony of this is that the goal is interdependence, not individualism. It’s about inviting people into the conceptual underpinnings of the work through the story-telling, not using that to demonstrate intellect or ability.